Breathing and core strength, in posture and everyday life

What is Core Strength?

There is no fixed definition of Core Strength, and any different opinions exist. We could think as core stability as “the ability to return to neutral posture, controlling the force produced by core strength.”

Core strength:

The strength of the underlying muscles of the torso, which help determine posture.

The ability to produce force with respect to core stability.

Core stability:

The capacity of the muscles of the torso to assist in the maintenance of good posture and balance,

especially during movement.The ability to control the force we produce.

Four Layers of Abdominals

One popular myth I’d like to dispel is that abdominal crunches comprise core strength — these exercises are valuable in small doses, but done to excess only overwork the most superficial layer, the six pack, also called rectus abdominus. Conversely, the transverse abdominus (TA) comprises the deepest layer of the core (closest to the spine). It is part of the deeper core, which fires up in anticipation of the movement to come. Studies have shown that among those who suffer from lower back pain, the TA is not firing in a timely fashion.

Six Pack Abs (rectus abdominus) are a component of superficial core = closest to the surface. They become dysfunctional when they are trained as prime-movers in isolation from the rest of the body (as in sit-ups). This can flatten your natural lumbar curve, mis-align the disks and compress them. Healthy abdominals are meant to work as back stabilizers - they support and protect the lower back.

Obliques (internal and external): Involved with rotation and side-bending (lateral flexion). These lie closer to the spine than the rectus abs. The obliques can also be used as muscles of forced exhalation. When they tone to much, this can inhibit the ability of the diaphragm to guide efficient respiration, setting off the fight-or-flight response. But among those who have mastered breathing, the obliques can be used without having a negative impact on the function of the diaphragm.

Transverse abdominus (TA): The TA is like a corset that stabilizes the trunk,and plays a major role in healthy movement. Transverse abdominus is part of the deep core musculature, which means that it’s closer to the spine and plays a great role in stability. Although the TA is involved in all healthy movements, one of it’s more notable qualities is allowing us to maintain the natural curves in our spines while tensing around the abdomen.

In more relaxed yoga postures, we isolate the lower portion (below the navel and above the pubic bone) from the upper fibers. This is confusing either called mulah bandha (root lock) or uddiyana bandha (diaphragm lock) by different teachers of the same traditions. This problem comes down to more than language games - there are at least two ways of applying each type of bandha in the body, which I’ll be disucssing in my next blog post.

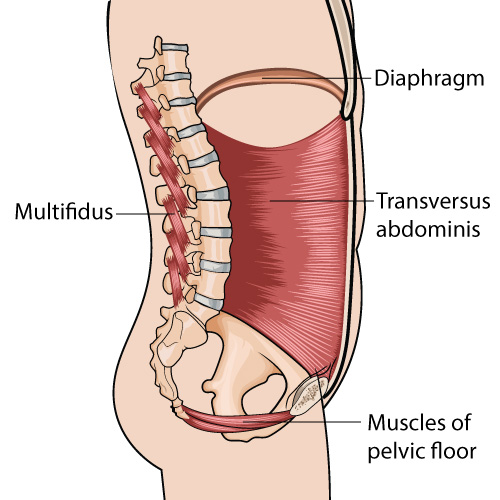

Deep Core Strength

Deep core refers to muscles closer to the spine itself which will play a strong role in stability, protecting the joints as we work with forces our bodies create or interact with outside forces.

The following three deep core connections work in concert to create stability BEFORE the movement occurs.

The transverse abdominus (described above) is the only of the four abdominals layers considered among this category. Like a corset, in wraps the torso with most it’s fibers running horizontally.

The multifidus are stabilizing spinal muscles that run the length of the spine, close to the midline. They stabilize each individual vertebrae to prevent disk degeneration that can arise from too much movement in any one joint. Healthy movement involves a little bit of movement in a lot of different places.

The pelvic floor is the floor of the core. It tones to help keep organs in place. When it is weak or dysfunctional, the body is unable to safely generate intra-abdominal pressure. More on that below.

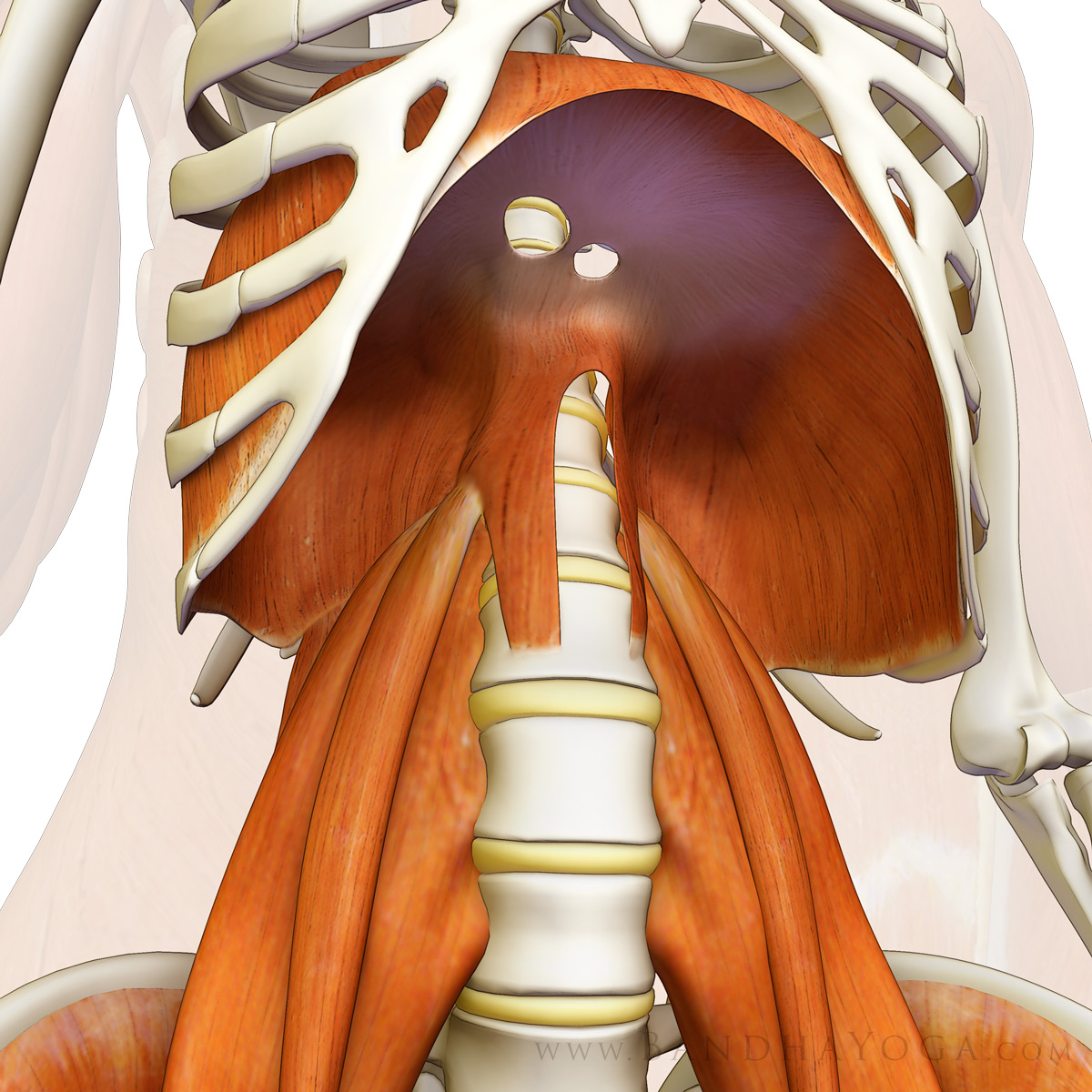

The Diaphragm

The Diaphragm is the main muscle of breathing. The diaphragm contracts automatically to draw in oxygen when we inhale. While we generally don’t control the action of the diaphragm, we can learn to regulate how quickly it contracts or releases by working with the pelvic floor and muscles in the throat.

Advanced breathing exercises in yoga (kriyas and pranayama) may involve inhibiting the diaphragm while holding the breath out, or slowing it down using abdominal core muscles and other accessory muscles of respiration around the shoulders and ribs — this is one of the reasons why pushups are a pre-requisite to advanced breathing techniques.

In movement practices, we can take advantage of the pressure changes created by inhaling to protect the spine and perform physically demanding exercises with greater ease. This technique is referred to as generating intra-abdominal pressure. The basics of this technique start with breathing slowly into the abdomen while doing push-ups, or lifting into crow pose, a form of mulah bandha. A more advanced application of mulah bandha involves breathing in less than 20% of one’s available capacity while lifting into a handstand, and then holding the breath. This makes the body much lighter, and also offers protective benefits around the lumbar spine.

A tight psoas will effect the position of the lower back, and prevent the back portion of the diaphragm from expanding properly. This can often be seen as bulging the belly out on an inhalation, or felt as a more shallow breath that expands the chest.

Releasing the psoas allows the inhalation to gently expand the lower back. The resulting increase in intra-abdominal pressure offers protective benefits for the lumbar-sacral area, and makes the body feel lighter in weight-bearing movements. Gentle breath linking movements are the ideal training group - the practice of vinyasa yoga.

The Psoas

The psoas is an often overlooked part of core strength. It attaches from inside of thigh bone (femur) to the lower back (all lumbar vertebrae) as well as the lowest thoracic T12. The psoas is often thought of as a hip flexor, commonly weak, tight, and dysfunctional from too much sitting. Research shows it can also act as a hip extensor in some individuals, depending on which vertebrae it attaches to. Because of this contradiction, researchers classify it as a core stability muscle.

The muscle of floating that allows fluid, flowing movement, like water. A healthy psoas is both flexible and strong. It always maintains resting tone, and functions both in core stability and as a hip flexor in the walking-phase. It also can function as a very weak external rotator.

Excessive tone is released when a harmonious relationship is found between alignment and stability, recruiting the deeper core muscles mentioned above, along with hip extensor muscles (hamstrings and gluteals).

Pelvic Floor

As the floor of the core, the pelvic floor muscles also need to be trained to acquire the right amount of resting tone. The most common mistake is “pushing down” as if going to the bathroom. In some situations, kegel exercises can be helpful, but they don’t guarantee the correct type of recruitment of the musculature.

In basic terms, create the sensation of an upward squeeze in the pelvic floor. Focus on this while exhaling. Traditional yoga texts like the Hatha Yoga Pradipika offer the imagery of breathing up the central axis of the spine, from the pelvic floor up through the throat or crown of the head. This notion of drawing energy up the spine on inhalation is a sure sign of a toned pelvic floor.

Cues for deliberately activating the pelvic floor can be helpful in the beginner. They also differ between men and women due to anatomical differences:

For men: Imagine “sending the boys home,” lifting the testicles. Another cue is to “shorten the shaft.”

For women: “Think of vagina as a clock with 12 at the pubic bone and 6 at the tailbone; also imagine the sides the sides of vagina as 3 and 9… Draw 12 to 6 and 3 to 9.

For everyone: “Imagine the pubic bone and tailbone dropping in relationship,” as Richard Freeman says.

A well-trained pelvic floor has a natural resting tone. Once it’s been trained to go online, it is not necessary to think about it. Consciously squeezing the pelvic floor muscles can be a helpful strategy in the short-term, but over the long-term we can let go of any technique and simply focus on breathing up the central axis, as in the various forms of uddiyana bandha I’ve described in other blogs here.

It’s equally important to do restorative practices where the body is fully supported, and you can focus on consciously relaxing the pelvic floor.